‘The Climbers’ Club’ – the First Ten Years with extracts from the

CCJ

Throughout the late 18th and into the 19th Century the mountains

gradually lost their terrifying reputation for being the home of dragons,

witches and wizards who hurled their victims down the precipices only to be

devoured by the Devil lurking in the surrounding valleys. People were beginning

to viewing the mountains with alternative aspirations in mind.

During

the Victorian period the sporting world, especially in the British Isles was

beginning to get itself organised and structured in more formal ways. The

Victorian middle-class gentleman were taking the ancient pastimes of village

life, adapting them, codifying them, and organising them into virtually all the

modern sports as we know them today. The Football Association was formed in 1863

and the Football League in 1888. County cricket matches were first played in

1873 and the first Test Match in 1880. Lawn Tennis was ‘invented’ in 1874. By

1885 golf was becoming popular. Rugby Union rules were established in 1871 and

boxing had the `Queensberry Rules’ by 1880. Was it so unexpected that the

adventurous men of the time, and only a little later the women, developed

organisations for mountaineering, walking, climbing, pot holing, and sailing?

One

of the earliest groups to show a specialisation in the ‘technical’ scrambles of

the day was the Scottish Cobbler Club formed in Glasgow in 1866. Many of these

climbing clubs and associations were chiefly established to provide `training’

opportunities for their members interested in further exploring the Alps and in

particular the more technical lower peaks that had, up until then, not had an

ascent. In 1857 the Alpine Club was formed by several British mountaineers that

had been particularly active during, what is known as the `Golden Age of

Alpinism’, 1854–1865. Several of the new clubs were formed, as would have been expected,

by a nucleus of Alpine Club members living in Scotland and who were to go on to

bring about an awareness of what the Scottish hills had to offer the

mountaineer and climber.

One

for the founder members of the Alpine Club was a wealthy solicitor from

Birmingham and a political friend of the Chamberlain family. C E Mathews first

visited Pen-y-Gwyrd in 1854 from where in the spring of that year, and for the

first time, he ascended Snowdon and like so many of us today, he went on to

become a regular visitor, for nearly the next

fifty years, to ‘the Gwyrd’ and North Wales. Mathews, with his experience of the Alps had made a lot of friends

who were foreign `professional’ mountain guides and he played a major role in

introducing the Alpine Club to North Wales and in particular `the Gwyrd’.

The Society of Welsh Rabbits

The

ranks of British `Climbers’ and `Alpinists’ continued to expand rapidly and in

1870 Mathews formed the ‘Society of Welsh Rabbits’, the name being synonymous

with the breeding habits of those little furry creatures. The object of the

Society, whose natural birth was at the Pen-y-Gwyrd, was to explore

Snowdon in winter and as near to Christmas as possible. By then, during August

and September, and in most years, a group of men who rarely met anywhere else

would gather together to share their mutual enjoyment of the hills and at the

end of the day, after a fine meal, they would sit round the fire and share their

experiences, the older men would drop encouraging words to the beginners,

difficult ‘points’ [of a proposed route] would be discussed and located and suggestions were made for the

following days climbing. This group of men were well aware of their common

grounding for George B. Bryant, in the CCJ Vol. 1 No.1 August 1898 goes on to say, `In

that congenial atmosphere, where conventionalities were not obtrusive, and the

bishop or the man of law shared the sofa with the old shepherd and deferred to

his opinions, men of various sorts, but united in their love of the mountains,

grew to know each other; and there the sense of association, the germ of the

Club, struck its first root.’

This

band of explores rapidly multiplied, as rabbits do, and soon the professional

upper class regulars suggested meetings in the summer as well as during the winter

months.

|

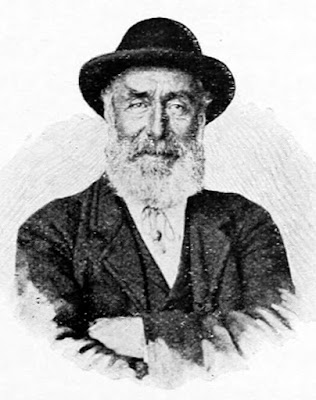

| The famous Swiss Guide of the time, Melchior Anderegg |

The

majority of the higher ‘less technical’ summits of the Alps had all been

climbed by 1885, in their entirety as guided parties but with the vast majority of those parties being

made up of Englishmen. New Alpine districts, where the lower less technical peaks

had yet to receive their first ascents, were now the focus of attention. Many of

the young British mountaineers visiting the Alps had aspirations to make

ascents of these lower technical summits and many would employ the same guides

and would in fact make recommendations to each other as to who would provide

good service, usually via the Alpine Club meetings. In April 1888 Mathews

arrived at the Gwyrd with Melchior Anderegg, the great Swiss Guide and climbed

Snowdon, Anderegg wanted to turn back from Crib Goch not expecting to reach the

summit in less than five hours but Mathews assured him it would be possible in

four. The pair summated in four hours five minutes!

It

was generally felt that the Pen-y-Gwryd ‘Welsh Dinner’ meets were spaced too far apart

so a suggestion was thrown out that these intervals should be bridged by a

dinner in London. This was met with instant enthusiasm and so the first CC London

Dinner was held on the 19th May 1897 when about forty of the Welsh

farm-house regulars gathered at the ‘Monaco’ Restaurant to `recall old times’, with

T S Halliday, one of the Club’s forefathers presiding over the gathering. At

the time it was doubted whether the actual formation of a Club was likely to take place, however there was a strong desire at

that meeting to continue with the Welsh Dinner and it was planned to again hold

this function in December 1897 at the Pen-y-Gwyrd.

By

the time the second dinner, and first Welsh Dinner, came round there was a

strong feeling from many quarters that the formation of a club was being

welcomed. The proposal was put forward and on the 6th December 1897

the first official Welsh Dinner took place. Unfortunately, as happens even today, this

date was not convenient for everybody and several regular and long standing

attendees of the previous Welsh Meets were unable to attend, amongst them C T

Dent, Frederick Morshead and F T Bowring. However the general attendance was

good and the foundations of the Club were laid down. The resolution `That a Climbing Club should be formed’ was

proposed by Roderick Williams and seconded by H G Gotch, both Alpine Club

members, and was then accepted by those climbers present under the chair of the Rev. J N Burrows. Those general members present included Roderick Williams, Lord Coleridge,

C E Mathews, Arthur J Gale, T S Halliday, H G Gotch, Thomas Rhodes, A O

Prichard, C C B Moss, A F Leach, L K Pagden, H A P Genge, J Fildes Pearson, E W

Chaplin, G H Chaplin, Astley J Morris, W W R May, Marshall J Smith, Charles

Candler, Dr E C Daniel , Henry

Candler, Dr T K Rose, C

Hampton Hale, Frank Pearson, George B Bryant, E R Turner and William Ernest

Corlett. This collection of climbers’ were generally referred to as the

‘Forefathers’ of the Climbers’ Club and they then went onto elect C E Mathews as

the first `CC’ President with Frederick Morshead and F H Bowring as Vice

Presidents, George Bryant as Secretary and Dr T K Rose as Treasurer, the

genreal committee consisted of W G Corlett, Rev J N Burrows, W Cecil Slingsby, E

R Turner, T S Halliday, and Roderick Williams. The Club at that time had a

membership of forty but there was an assumption that numbers would increase

within the first year to one hundred.

CE Mathews’ Presidential Years 1898 – 1901

In

March 1898 the CC Committee issued a circular promoting the Club

The Climbers’ Club

25th March 1898

Dear Sir,

It has been determined to establish a Club under the above title.

The object of the Club will be to encourage mountaineering, particularly in

England, Ireland and Wales and to serve as a bond of union amongst all lovers

of mountain climbing.

The qualification for members will be determined by the Committee,

who will have sole power of election

The officers will be a President, two Vice-Presidents, an Honorary

Secretary, and an Honorary Treasurer. The Committee will consist of the

officers and nine additional members, all to be elected annually at the Annual

Meeting. The first officers will be: -

The President C

E Mathews

Vice-Presidents Frederick

Morshead

F

H Bowring

Hon Sec George

B Bryant

Hon Treasurer T K

Rose

The Annual Subscription will be half-a-guinea, and after there

will be an entrance fee of the same amount after the first hundred members are

elected.

The Annual Meeting will take place in London at the end of April

each year, and will be followed by a Dinner. The First Annual Meeting and

Dinner will take place about the end of April next, on a day and at a place,

which will be duly notified.

The Club will be in no sense antagonistic to any existing

institution; but will, it is hoped, gather all those who are interested in

mountaineering in England, Ireland and Wales.

Should you be willing to join, will you be good enough to return

the enclosed form immediately to: -

Mr C E Mathews, The Hurst, Four Oaks, near Birmingham

At the First Annual Meeting the Formal Laws of the Club will be

presented for adoption, and the First Annual Dinner will follow.

Yours faithfully,

C E Mathews

Frederick Morshead

F H Bowring

George B Bryant

T K Rose

[CCJ

Vol. 1 No. 1 August 1898]

This

circular was sent out to all those people known as `climbers’, whose names

could be obtained from various sources, including from those who were already

CC members. The response exceeded expectations with exactly two hundred

applications for membership being received by the day of the first AGM.

Although this doubled the number that the Committee had previously agreed to admit

without an entrance subscription there was no option other than to admit all

two hundred as ‘original members’ of the Club.

The

first AGM was held in the Alpine Club rooms in Seville Row, London on the 28th

April 1899 attended by the President and sixty-two members. The rules of the

Club were agreed and passed and the officers of the new committee were formally

elected; The President, C E Mathews, Vice-Presidents Frederick Morshead and F H

Bowring, The Committee, Rev J N Burrows M A, W C Slingsby, Roderick Williams, Owen

Glynne Jones, R A Robertson (President SMC), H G Gotch, E R Kidso, E R Turner, W

P Haskett-Smith, Hon Sec George B Bryant and Hon Treasurer T K Rose.

|

| Early Climbers' Club members, Mathews third fom the left and Eckenstien and Robinson right top row |

In

line with the developments being made by the Scottish Mountaineering Club it

was proposed that the Climbers’ Club should ‘have

a view to expand its interests in the directions of botany, geology, art and

natural history.’ After the AGM the Committee and Members reconvened at the

Egyptian Room of the Monaco Restaurant where all eighty members were individually

announced before dinner.

During

the Presidential speech C E Mathews made reference to the formation of the

Alpine Club forty-years previously and the fact that its first dinner was only

attended by twelve members from an original membership of thirty. He also

mentioned that the Alpine Club had published a series of articles, `Ascents and

Adventures’, and that the Club, its members, and its publications had received

from an `undiscerning public ridicule, disapprobation and contempt’.

This in the main came from Anthony Trollope in his `Travelling Sketches’ but

more viciously was the onslaught from Ruskin who accused the Alpine Club of ‘Making racecourses of the cathedrals of

earth, the Alps which your own poets used to love so reverently, you look upon

as soaped poles in bear gardens, which you set yourselves to climb and slide

down with shrieks of delight.’

| |

| Walter Parry Haskett Smith |

Mathews

then went on to add `The critics did not

know much about it. There is a story told of a certain undergraduate, not very

well up in his Greek, who told his tutor that he had contempt for Plato.’ ‘I should presume, Sir,’ said the tutor

’that yours is a contempt which does not proceed from familiarity.’ [CCJ Vol. 1 No. 1 August 1898]. This was a reference to Haskett-Smith who was

reading Literae Humaniores at Trinity Oxford when he first discovered Wasdale

and who was sat in the gathering to hear the Presidential speech.

`Criticism is good for all of us, but it is

really valuable in proportion to the honesty and ability and insight of the

critic. That Club, with a steady rising standard of qualification, now numbers

over six hundred men; the great hall at the ‘Metropole’ is not large enough to

accommodate the numbers that flock to its winter dinners; and it comprises

within its ranks some of the best of intellectual aristocracy of this country’.

He went on ‘that a man who only sees what

is just before his eyes loses always the best part of every view; but we have

neglected too long the binding together of the lovers of the beautiful scenery

at our own doors. The Scottish Mountaineering Club first realised the

situation; then the Yorkshire Ramblers; and last year; the Climbers’ Club had

been founded, which embraces England, Ireland and Wales, and yet is open to all

lovers of mountaineering in every quarter of the globe. At last our

mountaineering ladder is complete, and the youth of England can be reassured.

They can matriculate at the Climbers’ Club; they can graduate in the Alps, and

carry off the highest honours in the far-off regions of the Caucasus and the

Himalaya. We have begun well. We begin two hundred strong. I will not say every

original member has an ample mountaineering qualification. But we have no

reason to be ashamed; one-third of our members are also Alpine Club men – a

good healthy sign’. Mathews then went onto identify `seven members from The University of Oxford, seven members from

Cambridge, the Bar was represented in great force, Davidson was the legal

advisor to the Foreign Office and thirty gentlemen have joined us from what is

erroneously called ‘the lower branch of the profession.’ ‘The Scottish Mountaineering Club, The

Yorkshire Ramblers each contributed its president. Climbing literacy is

represented by Haskett-Smith and Owen Glynne-Jones, we have authors,

journalists, clergymen, members of the Civil Service, merchants, manufacturers

and inspectors of schools. I see undergraduates from Oxford and Cambridge here

tonight, who, I trust have obtained the usual permissions from their tutors;

and the best bowler in the Oxford Eleven has placed his services at our

disposal’. ‘Of such excellent

materials is the Climbers’ Club composed’. [CCJ

Vol. 1 No. 1 August 1898]. Mathews concluded, ‘And

so, I give to you ‘The Climbers’ Club!’ Remember that a Club is an institution

towards which every man must contribute his share. May it flourish and prosper!

Mr

Roderick Williams responded to the toast, ‘Our

hills and mountains.’ `This ‘plain tale’

ends for the present with the result of a Committee meeting in June at which it

was decided to publish a Journal at the expense of the Club once every three

months, Mr E R Turner undertaking the editorship. The membership has now

reached 209 and there are several applications to be dealt with at the next

Committee meeting.’ [CCJ Vol. 1 No. 1 August 1898]

|

| Wasdale Head Hotel |

The

Committee had soon realised the importance of the annual meeting as playing a

considerable role in keeping the Club together and provided the opportunity for

all members to meet together under one roof. To develop the Club’s ethos the

Committee organised meets in various climbing areas and, as an experiment, designated the mid August to mid September period as being an opportunity for

members to attend a meeting either based on the Pen-y-Gwryd or in Wasdale. It was

thought advisable to avoid a concentration of the membership at any one place

so as not to `outrun the available

accommodation’. It was a condition of the meets at that time that a journal

or log book would be kept detailing all activities and that at the end of the

meet it should be forwarded to the Honorary Secretary as the property of the

Club. Suggestions for future arrangements could also be made through the log which

would then be available to the Editor of the Club Journal to be used at ‘his

discretion’. The Committee also considered a winter or spring meet with Easter

being considered the best choice for ‘winter’ conditions to be found in the

gullies. The next matter the Committee referred to was that of the question of

whether or not the Club funds were sufficient to enable the Club to secure

permanent rooms for the exclusive use of the Club in London. The outcome, after

discussion, was that there were insufficient funds and at that point the

question was raised as to whether such rooms were actually deemed necessary?

|

| Oscar Eckenstien |

Oscar Eckenstein,

who had a great deal of mountaineering experience by the time he joined the

Climbers’ Club in 1898, became the first man to carry out a serious analysis of

climbing techniques and equipment. He invented and demonstrated the 10 point

crampon and also designed a shorter ice axe, just over two feet (60 cms) in length which

was considerably shorter than the traditional alpenstock used by all the

alpinists of the time. Amazingly his ideas fell on deaf ears, principly because he was a quiet man and shunned publicity, it was not

until many years later that the ‘new’ technology was eventually put to the

test. Eckenstein became a close companion of J M A Thomson and for nearly

twenty years the latter completed many first ascents, eighteen new routes on

Lliwedd and sixteen other climbs on Tryfan, Glyder Fach and Glyder Fawr and

fourteen new routes in the Llanberis Pass.

Lliwedd was Thomson’s favourite `cliff’ with his

notable ascent of Avalanche Route being one of his best achievements, so called

because of the boulders knocked down by a young G L Mallory from above during

the first ascent. Thomson climbed into his fifties and in 1911 put up a new

route on Skye. He suffered two nervous breakdowns and eventually whilst alone

at his brother’s house in Surry drank carbolic acid, two hours later he was

dead.

|

| Oscar Eckenstien, shunned publicity |

It

is interesting to note that in the second edition of the CCJ November 1898 Owen

G Jones states that `we must be prepared

to admit without much qualification that there is no more room, and that there

are not many problems remaining unsolved, on high days and holidays, the hotels

are overcrowded and the outhouses filled to overflowing. The popular gullies

are thronged with visitors. It becomes almost necessary to issue numbered

tickets to the waiting throng at the foot of Gable Needle. Orders for the

ascent of Kern Knotts may be received two days in advance; this is a fact in my

own experience’. What would he make of the situation today?

Along

with Jones assessment of the state of English climbing he shows a great

knowledge and understanding of alpine ‘scrambles’ comparing for example the

traverse of the Dent du Requin to the Ennerdale face of great Gable or ‘the Pillar Rock by the North Climb giving as

much rock work as the Portiengrat traverse, the Zinal ridge of the Rothhorn, or

the Wandfluh ridge of the Dent Blanche’. [CCJ November 1898 p 29]

From

the time of the original concept of forming a Climbers’ Club a group of men ‘with a mutual and vested love of the

mountains’ would meet regularly in north Wales. By the time the second

edition of the CCJ was circulated the first ‘official’ meets had been held with both the

Pen-y-Gwryd and Wasdale being the hub of activity. A Climbers’ Book was started

for the use of climbers in January 1890 and kept at the Waswater Hotel. Today these two hostelries still feature

greatly in the list of any genuine outdoor enthusiasts’ must visit venues and

with the aid of a small glass of the amber nectar one can still sit quietly and

be in the company of other great 'spirits', but as our friend O G Jones stated ‘it’s best to avoid high days and holidays!’

|

| An early ascent on Welsh rock (route unknown) |

In

the report of the first meets of the Climbers’ Club it is stated ‘the majority of climbers appear to prefer

trying some well-known gully or face rather than to strike out new routes for

themselves. That this should be the case amongst the Cumbrian hills is scarcely

surprising; indeed there where every chasm has received a name, and every

needle and pillar is, figuratively speaking, dotted with routes, it is

difficult for anyone who is not an expert to make a first ascent. But it is not

so in Wales. The Cambrian hills have not undergone the systematic examination

that has been accorded to their English rivals. A striking instance to this is

Clogwyn du'r Arddu, the magnificent precipice along which the Pony Track

zigzags its way up to Y-Wyddfa. If this precipice were situated within easy

walking distance of Wasdale Head, it would probably have a literature of its

own; but as it is, it suffers from ill-deserved neglect, and is comparatively

unknown’. Little was he aware that many years later Ken Wilson would fill

that gap with `The Black Crag’.

During

the first Wasdale meet on the 10th September club members made the

first ascent of the West Wall Climb of Deep Ghyll and on the 23rd

Great Ghyll succumbed to the CC onslaught in ‘rather damp conditions’.

Of

the two meets it was the Welsh one that drew the greater numbers with members

beginning to arrive in early August with the season finally drawing to a close

in late September. During this time ‘a

considerable’ amount of climbing was done with exploration taking place in

the Tryfan gullies, Glogwyn-y-Person, the gullies up Esgairfelen, Lliwedd and

Crib Goch all received inspection. Snowdon had its fair share of visitors with

reports of ‘several pitches of very

severe’ being attempted.

It

is apparent from earlier comments in the journal [November 1898] as to the fact

that existing ‘traditional’ climbing areas were thought to be almost worked out

and that club members were actively searching out new parts of the country in

which to develop climbing activities.

Ernest

Baker begins his article `Practice Climbs in Derbyshire’ by apologising for

writing a ‘paper’ on a series of scrambles of less than a hundred feet in

height, `were it not for the fact that

they are in the neighbourhood of some of the most attractive scenery in

England, and right at the gates of several of our biggest towns; the man who

happens to tumble off a big boulder may hurt himself, but he will not have the

luxury of falling through a thousand feet or so of magnificent scenery.’

Baker goes on to wax lyrically about the fact that Northern Derbyshire

possesses a miniature mountain-system, amid which many `capital little scrambles’ are to be found. Haskett-Smith adds his

voice of approval by noting that ‘When it

does offer a climb, it ends it off abruptly, just as we think the enjoyment is

about to begin.’ He goes on to specifically mention Froggatt Edge, just

above the Chequers Inn, ‘where there is a

remarkably good crack, only giving a climb of 40 or 50 feet though.’

Mention is also made of possibilities to be found in Leicestershire and

Nottingham. [CCJ November 1898 p 55]

The

chapter concludes ‘Although the

Derbyshire scrambles are nothing more than practice scrambles, it is not to be

forgotten that, like all other climbs, they are to be found amidst delightful

landscapes and at the end of inspiring walks. For their purpose they are

first-class quality, and a man might serve an apprenticeship here in his off

time, which would qualify him to undertake some of the best rockwork in the

neighbourhood of Sligachan and Wasdale Head’. [CCJ November 1898 p 29]

In

line with the recommendation that the Club should broaden its activities to

include botany, geology, art and natural history there is a paper researching

‘The Glyders and Thermometers and Winter Temperatures on Mountain Summits’ by

Piffe Brown. In it he documented thirty years of evidence 1867 to 1897 where

the lowest temperature were recorded as being -8.0°F with the average temperature

being 16.02°F. [CCJ February 1899 p80] I wonder how this equates to the global

warming temperatures of the 21st Century?

|

| A modern ascent of Devils Kitchen |

The

first ascent of the Devil’s Kitchen took place on the 3rd March

1895, although this was before the official formation of the Climbers’ Club

would be Club members were involved in this winter ascent. Llyn Idwal was

covered by seven inches of ice making the approach a straightforward

affair. Progress was achieved with the

use of a ‘hatchet’ that enabled Hughes and Thomson to penetrate the wall of ice

that they supposed was solid through to the back wall of the chimney. However

on creating a hole through the ice it became apparent that the ice was in fact

a free standing curtain hiding a large cavern behind which Thomson estimated to

be 10 feet in diameter and reaching 20 feet up from the place of entry and

30 feet down but owing to the darkness the bottom was not visible and so the

last measurement was only a wild guess. As the prospect of a rapid and

uncontrolled fall into the cavern loomed large in his conscious mind Thomson

continued climbing on the outside of the curtain aware that the ice was not a

particularly solid structure. Hughes initially formed a portable belay ledge

from which Thomson could climb but he then felt that in case of emergency he

would be better employed as a sheet anchor back down inside the cavern. This

must be one of the earliest attempts at steep ice climbing. Thomson went on to

explain how difficult it was using the hatch in such cramped conditions where

it was almost impossible to deliver each blow with accuracy and at the same

time to protect his head at the moment of impact to allow the ice fragments to glance

off his skull as opposed to hitting him full in the face. By the time they

reached top of the wall the thickness of the ice had diminished to only about

an inch but was strengthened by the icicles forming ribs. At this point it was apparently

possible for Thomson to use his axe, which was presumably considerably longer

than the hatchet so as to reach the snow slope above and to cut a step. He

estimated that the angle of the slope to have been 80 degrees. This pitch must

have been in excess of 80 feet because Hughes had to leave his belay position

to allow sufficient rope for Thomson to reach the end of difficulties. It had

taken him three to complete the hard climbing. By the time Thomson and Hughes

reached the true top it was 7.15pm and intensely cold and dark. The initial choice

of the descent route was to go down to Llyn Idwal but due to the increasingly

steep ice they decided to retreat over the plateau and down into Llanberis

where they reached the Dolbadarn Inn at 10.30pm. [CCJ February 1899 p85]

|

| George and Ashley Abraham |

Halfway

through Thomson’s climbing career a young fit and muscular man began to take an

interest in the hills and in particular in rock climbing. Owen Glynne Jones

made his first ascent, and solo, of the East Arete of Cyfrwy on Cader Idris.

Jones had done much in the Lake District and his book relating many of his

experiences and adventures ‘Rock Climbing in the English Lake District’ was

published in 1897. Jones met two young brothers from Keswick and introduced

them to the wonders of climbing, the Abraham brothers. Early in 1897 Jones took

the Abraham brothers to Wales and introduced them to the Pen-y-Gwryd scene. By

now George and Ashley Abraham were almost as skilful as Jones and they

undertook many exploratory climbs together. On one occasion all three attempted

to ascend Slanting Gully on Lliwedd but failed. Jones then had to return to

Wasdale to keep a prior commitment, leaving the brothers he warned them to stay

away from ‘his’ route, Slanting Gully. Shortly after, on the 27th

April, George and Ashley set off reputedly to ‘potter around on Lliwedd’ and

then made an attempt to claim the first ascent of OG Jones’ route. Upon their

return the Abraham brothers were not made to feel welcome at the Pen-y-Gwryd,

the established upper middle class did not like to see them complete a number

of new routes on a variety of cliffs, especially if they had been tried by

other members of the group. This was partly due to envy but the predominant

feeling of disassociation came from the fact that the brothers were not only

professional photographers but ‘shopkeepers’ as well. The Abrahams did not help

the situation or the fraternity of the Pen-y-Gwryd when they published their

book on ‘Rock Climbing in North Wales’. However both brothers, George and

Ashley gained membership to the Climbers’ Club by the end of its first year.

During

Easter 1899 Jones and a large party of climbers went to Wales to continue their

work on the ‘Rock Climbing in North Wales’ book. Jones completed the first

ascents of the Devil’s Staircase and Hanging Garden Gully. Milestone Buttress

was the next venue for the group and although they attempted Belle Vue Bastion

they failed but did successfully complete what is now called Cheek Climb and

Terrace Wall Variant. At the top of the Devil’s Staircase Jones and George

Abraham discussed plans to go to the Himalaya, sadly this never came to

fruitarian as within six months Jones was tragically killed on the Dent

Blanche.

|

| The Tooth and Needle, Beachy Head |

The 1899 CCJ contains an article by H Sommerset-Bullock on the virtues of climbing on Beachy Head. That autumn must have had particularly bad weather conditions for in the ‘Notes from Wasdale’ it is stated that Borrowdale ‘had been the venue of some extreme flooding with the Seathwaite road being under some five feet of water, the path from Sty Head being obliterated' and in summing up it is mentioned that 'the flood, the severest for thirty years or more had ‘swepted the scheme for the Sty Head carriage-road into the middle of the next century, sufficiently far off at any rate for it to remain out of sight and out of mind for many years to come’. However by Christmas the weather must have settled as Abraham and Field were led up Walker’s Gully between Pillar Rock and the Shamrock by O G Jones to complete the first full ascent on the 7th January 1899.

The

first article to appear in the CCJ that dealt specifically with a foreign expedition

did so in Vol 1 No.4 June 1899 and was titled `A High Level Walk from the

Brenner to the Bernina, Without Guides’ edited by Henry Candler. This article

deals in some considerable detail with the route, the views, acquaintances and

the occurrences of the expedition. [CCJ June 1899 p 133]

The

notes of the AGM held on the 5th May 1899 recalls the fact that

Bowring retired from his position as Vice-President due to ill health, this

fact gave rise to a feeling of great regret as Bowring was one of the earliest

of English rock-climbers, E A Robertson, President of the Scottish

Mountaineering Club, was elected to fill the position. All other officers were

re-elected. The accounts for 1898 were accepted as audited and showed £73 2s 6p

as balance in hand. Guests at the dinner included Sir W Martin Conway, Dr HR

Dent Sidney Lee and C R Canney. In his Presidential speech Mathews pointed out

and recognised that ‘Boat-racing was

practiced by thousands and that cycling had been the saviour of the wayside

Inns and that it had restored to the English people the beautiful roads and

lanes of our common country which the railways had taken away. Football was not

only popular, but its exhibitions are attended by millions. How was it that

mountaineering was the noblest pastime in the world? How was it that scholars,

and statesmen, bishops and deans, men of science and men of letters, senior

classics and senior wranglers, had found the best solace and recreation amidst

the gloom or the glory of the hills? The reasons he declared were not difficult

to see. ‘We get renewed vitality from

personal contact with our mother earth in her best and noblest form. If we

could not reach the Himalaya, the Andes, or the Caucasus, the blessed Alps were

within easy reach of us, pure, bracing and invigorating. And if even these were

too remote from some of us, remember that Helvellyn and Scawfell were only a

day’s journey from London, and that God created Great Wales!

Haskett-Smith responded in lighter tones, R A Robertson, the new

Vice-President replied in a more humorous style commenting that ‘the government of England had fallen into the hands of fellow Scotsmen

the ‘southerners’ had sought to avenge the situation by making numerous

unguided inroads into the even the most difficult of 300 difficult peaks over

which he presided in the Scottish Highlands. [CCJ June 1899 p 149] Maybe

this was a comment related to the fact that Norman Collie made the first winter

ascent of Tower Ridge on the 30th March 1894 to which Naismith wrote

-‘The Sassenachs have indeed taken the

wind out of our sails most notoriously I will say that. This is truly a sad day

for auld Scotland. .. Flodden or Culloden was nothing to this’ (undated SMC

Archives)

It

is interesting to note that Sidney Lee suggested that although he understood

ladies had not so far been considered eligible as members of the Climbers’ Club

it might be advisable, if not too late, to consider the desirability of

electing Queen Elizabeth (the Queen Mother), on account of the soundness of her

views, as expressed in the well known words with which she replied to the

aspirant who 'would climb did he not fear to fall'. Although this comment was in

essence made in jest it does support the ideas that in its formative years the

Climbers’ Club was not opposed to women members. [CCJ June 1899 p 149]

By

the time the CCJ was printed in September 1899 more articles were appearing

edited by members who were looking at distant ranges seeking out new adventurous

trips. Under the section titled ‘Welsh Notes’ the author enquired as to when a

book comparable to O G Jones ‘Rock Climbing in the Lake District’ was going to

be published. It was understood the O G Jones had been preparing a draft and questions

were raised as to the whereabouts of such a draft manuscript. It was also

suggested that a committee might be formed to undertake the completion of such

a book. Could this be the first

reference to the forerunner of the PSC or Guide Book Committee of today? [CCJ

September 1899 p 47] Although at that time there was not an Obituary section in

the CCJ note was made under Notes and Correspondence of the death of O G Jones

on the Dent Blanche. The brief obituary goes on to ratify O G Jone’s enthusiasm

and strong support for the formation of the Club and for his contributions to

the committee and to the Journal. Only a few days before Jones left for the

Alps he had discussed detailed plans for a Himalayan expedition and was

preparing the production of a book on Welsh Climbing. [CCJ September 1899 p 48] Under the Committee

Notes in the same CCJ a resolution was proposed by the Rev Nelson Burrows,

seconded by Haskett-Smith and unanimously passed, ‘The Committee desires to put

upon record its deep sense of loss which the Club has sustained by the death of

Mr Owen Glynne Jones, whose services upon the Committee have always been most

zealous and unremitting’

On

the 5th April 1896, O Eckenstein, H Edwards, H Hughes, W A Thomson

and J M A Thomson made the first ascent of Lliwedd’s East Gully and Buttress.

It had been the original object to lower one of the party down the crag to inspect

the line of the route so as to place beyond any reasonable doubt the questions,

which had been argued over during the previous evening, concerning the line and

difficulty of the proposed ascent. [CCJ December 1899 p 73]

| |

| Owen Glynne Jones Memorial Plaque, Evolene Church yard |

The

CC received notification of another association based in Derby, the Kyndwr Club.

There were several dual members of the Climbers’ Club and the Kyndwr Club but

the latter organisation was identified as a ‘club of scramblers’ pure and

simple, and so their love of outdoor science, archaeology, and even a congenial

interest in literature, enter into the ‘bond

of union’, and thus gave occasion for frequent meetings and excursions. [CCJ

March 1900 p 135]

The

Kyndwr Club Notes made their first appearance in the CCJ June 1900 p 178 which

consisted mainly of new recordings of scrambles around the Derbyshire edges.

This article appears 19 months after the previously mentioned Derbyshire

article by E A Baker, `Practice Climbs in Derbyshire’.

|

| Edward Whymper |

The

AGM of the 12th May 1900 was held at the Café Royal, London and was

attended by about forty members. The President reminded the meeting that he was

entering his third and final year of office. The audited accounts showed a

balance of £206 3s 6p in the bank. Amongst the distinguished visitors at the

dinner were Edward Whymper and A J Butler. The President began his speech with

the time-honoured toast ‘Success and

Prosperity to the Climbers’ Club’. During his speech the President Mr

Mathews questioned the circumstances of the ‘accident’ that befell Owen Glynne-Jones.

‘Gentlemen, I do not want to dwell upon

this particular catastrophe. I do not know what conclusions such excellent

authorities as my friend Mr Whymper or my friend Mr Morse may have formed upon

it, but, in my judgement, it was not an accident properly so called.’ He goes

on in his speech to say ‘may be that I am only a voice crying in the

wilderness, but I implore you, the mountaineers of the future, to do nothing

that can discredit our favourite pursuit, or bring down ridicule of the

undiscerning upon the noblest pastime in the world [CCJ June 1900 p 186] 1900

saw a longer than usual collection of after dinner speeches with over fourteen

pages of the Journal being used to report the events.

In

the Wasdale Notes J H Wigner reported that on the Good Friday 1900 several ‘unfit’ parties set out at great speed,

boldly facing mist and rain to attempt the Needle. Only two climbers (one of

them a lady) succeeded in reaching the top’. This lady however, was not

identified. [CCJ June 1900 p 199]

Over

the previous year many club members had expressed a wish that the Dinner could

be held in the North of England, the committee announced that the following

dinner venue would be in Birmingham. [CCJ June 1900 p 201]

In

September CCJ 1900 E A Baker describes how along with the Abrahams and J W

Puttrell they spent some days on Buchaille Etive Mor. It was in fact Puttrell

and Baker who were to inform this region of Scotland of the relief of Mafeking

decorating their transport with a pair of crossed ice-axes and assorted

handkerchiefs in jubilant celebration of the news. After initially reconnoitring

the mountain the team were pinned down by bad weather. A writer in The Scottish

Mountaineering Journal Vol. IV p150-1 reported, ‘At its lower end also, the rock that forms the crest of the ridge is

hopelessly steep, and nearly unbroken for some 300 feet. I will not prophesy

that that cliff will never be scaled in a direct line, but before then I think

mountaineering science will have to advance to a higher stage of development’.

Baker

describes the first of the main pitches as being about 70 feet long and of an

open nature, nearly vertical, and for the most part almost devoid of good

holds, those that did exist he reported were as being 'shallow and sloping the

wrong way, any upward movement would have to involve sustained balance'. The

next section required the team to un-rope thus enabling the distance between

each climber to be increased from the average 40 feet. George Abraham climbed

steadily for nearly eighty feet before he called for Puttrell to follow. Any climb

involving the Abrahams would automatically involve photographic equipment and

that expedition was no exception. Having done a hard pitch the rope was lowered

for the photographic equipment to be pulled up to a new vantage point. Ashley

Abraham pronounced the climb ‘to be at

least as difficult as Eagle’s Nest Arete on Great Gable’. After several

more exposed and seemingly hold-less pitches the group reached the summit via

the original Crowberry Ridge route. They then took the opportunity to have some

food before they began their descent arriving back at the Inn twelve hours after

setting out. [CCJ September 1900 p 3]

An

interesting article appeared in the CCJ September 1900 titled ‘A Wet Day At

Wasdale.’ This outlined the activities of those members ‘trapped’ by poor

weather conditions in the Wasdale Inn during the previous September, amongst the

activities described appears the ’Stable Traverse’, the ‘Billiard Room

Traverse’, the ‘Table Leg Traverse’, the ‘Bannister Traverse’ and possibly the

hardest of all the antics, in the hall, the ’Chimney Reversal.’ The author concludes assuring the reader that

‘there is no lack of amusement to be

found at the Inn even on the wettest of days’. Many of these activities are

now regular features at club dinners up and down the country.

In

the Committee Notice it was explained that consideration had been given as to

how to address the issue of detailing the mountain areas of Wales. The

suggestions put before the Club were that the country in question should be

divided into nine sections namely, the Snowdon Section, the Hebog Section, the

Glyders Section, the Carnedd Section the Arenig Section, the Rhinogs Section,

the Arans Section and the Cader Idris Section.

It

was proposed that a party should be co-opted to explore each of the nine

sections working as a group of six to an area. It was hoped that the data collected

would relate to geology, botany and physical features of the hills, and all

other facts of interest to ‘students of the mountains’, as well as those who were

more closely concerned with discovery, recording, and classifying the actual

climbs. If this idea was sanctioned by the general membership it was felt it might

in future be extended to other areas within the sphere of the Club’s

operations. [CCJ September 1900 p 39] It was also noted that the footbridge

over the Glaslyn River near Llyn Llidaw which had been destroyed earlier in the

year was to be replaced at the expense of the Club.

There

then followed a period of consolidation within the Club, the Journal continued

to develop and the breath of articles it contained expanded to include

reminisces from members’ climbing trips to the far-flung corners of the globe as

well as to include their exploits nearer to home. There was also a fair

coverage of scientific and geographical data presented by Club members.

The

first provincial dinner of the Climbers’ Club was held at the Queen’s Hotel,

Birmingham on Saturday 5th December 1900. C E Mathews was in the

chair and for those who could stay over Mathews organised a walk on the Sunday

in the Forest of Arden followed by lunch at his residence in Four Oaks.

The

last Journal to be published while Mathews remained as President is dated March

1901 and contained an article on the Rhinogs, G Winthrop Young writing on his

adventures during a very long winter’s day titled ’Benighted on Snowdon’, J M A

Thomson writes an account of a fatal accident on Tryfan. The interesting point

of this article is that the accident occurred just after it had been suggested

to Queen Victoria that she might wish to introduce a law to restrict mountain

and rock climbing as it was estimated 66 people had been killed at ‘lower

levels’ the previous year in the ‘pursuit of sport.’ As no journalists were

present at the inquest of the Tryfan incident there was an exceptionally high

level of inaccuracy reported in the newspapers.

|

| Lehmann J Oppenheimer Photo: Abraham Bros |

|

| WP Haskett-Smith 1936 on the 50th anniversary of his first and solo ascent of Napes Needle aged 76 years |

The era of W P Haskett-Smith 1901 - 1904

The

third Club AGM was again held at the Café Royal in London on the 31st

May 1901. This was to be the last meeting presided over by C E Mathews. The

incoming President was to be W P Haskett-Smith, of the two Vice-Presidents,

Frederick Morshead retired after his three years in office with George Morse

succeeding him. Members of the committee who retired by rotation were Cecil

Slingsby and Raymond Turner they were replaced in office by Professor J A Ewing,

an FRS of Cambridge. Dr T K Rose resigned from his position as Treasurer which

he had held since the formation of the Club. George B Bryant was re-elected as

Hon Secretary, the role of Treasurer was taken over by C C B Moss, the audited

accounts were agreed to be true and correct at £256.19s 1p. The after-dinner

speeches were again reported in full in the CCJ and cover some twelve pages, those speakers, taken from the ranks of officers and guests at the

dinner included, the President Haskett-Smith, the outgoing President C E

Mathews, Dr Owen on behalf of the guests, H G Gotch and on behalf of Kindred

Clubs, Lamond Howie and H Bond on behalf of the Kynder (Kinder) Club, and Mr

Wynnard Hooper.

June

1901 saw the first CCJ to be published under the new President W P Haskett-Smith

but the editorial responsibility remained with Raymond Turner who by now was

serving in his second year as editor.

|

| Napes Needle Ridge |

During

early 1881 a twenty-two year old was sitting in his rooms at Trinity College,

Oxford studying maps of England. He had been appointed by his groups of friends

to locate a suitable summer venue for the ‘reading party’. So it was that

Walter Parry Haskett-Smith first came to visit Wasdale, reading Plato in the

mornings and tramping the fells in the afternoon. It was on his first visit to

the Lakeland Fells, lasting two months, that he met F H Bowring, an experienced

hill walker who was to introduce the group to the excitement of the fells off

the beaten track. Haskett-Smith revisited Wasdale in 1882 with his younger

brother on a walking holiday, they explored cliffs and gullies. It was from

this point that climbing, as we know it was born. In 1883 Haskett-Smith took

his finals and gained a third class in Literae Humaniores, he was back in

Wasdale for a productive 1884 summer season but then in 1885 he went to visit

friends in the Pyrenees. 1885 was also the year that W C Slingsby first visited

Wasdale. At the time the Alpine Club had some scathing views about the Lakeland

Fells often regarding them as only worth consideration for alpine training

during the winter months. Slingsby was a member of the Alpine Club and had

repeated several of Haskett-Smith’s routes and these prompted him to write a

paper for the Alpine Journal dated the 6th April 1886 (although it

was not published until the following edition) in it he paid tribute to Haskett-Smith

as a ‘gentleman who has done much

brilliant rock climbing in Cumberland and who, unfortunately, is not in our

club’ (Alpine Club).

|

| Climbers on the East side of Pillar Rock, the scene of Jones' first Lakeland climb. Photo: Abraham Bros |

The

‘sport’ gathered momentum and from the outset Haskett-Smith was in the

vanguard. There was virtually no competitiveness between the climbers and

information was freely disseminated amongst the leading activists. The pioneers

became involved in rock climbing because they enjoyed the exercise, camaraderie

and danger (adventure). Haskett-Smith explored three main crags from Wasdale

where he achieved notable first ascents. On Pillar he discovered West Jordan

Climb and Central Jordan Climb (Aug/Sept 1882) East Jordan Climb, Great Chimney

(March 1884) and Haskett Gully in 1908. He then moved to Scafell and proximity

where he ascended Deep Ghyll in winter conditions (April 1882) Central Gully,

Great End (Aug/Sept 1882), South-East Gully, Great End (Aug/Sept 1882) Scafell

Pinnacle, High Man from Jordan Gap, solo (Sept 1884), Steep Ghyll, Low Man,

High Man (Sept 1884), Slingsby’s Chimney Route (July 1888). From Gable he

continued broadening his horizons, he visited Langdale and Coniston and was

responsible for the first ascents of Great Gully on Pavey Ark, North Gully on

Bowfell Buttress and North West Gully on Gimmer all within the two months,

August and September 1882. He then went to Dow Crag where he completed the

first ascents of ‘E’ Buttress Route and Black Chimney in 1886 and Great Gully

in 1888.

It

was whilst exploring Deep Ghyll that Haskett-Smith first saw Napes Needle

through a break in the cloud. The Napes Face of Gable was the last to be

discovered but once Haskett-Smith had ascended the Needle in June 1886 it

became one of the most popular and best-known routes which was widely

publicised by the stunning photographs of the time. Haskett-Smith was very much

a rock climber as opposed to being a mountaineer; he wasn’t necessarily

interested in reaching the summit. His ascent of the Needle was done solo in

the afternoon after a long walk and without the aid of a rope; it was the first

breakaway from the preoccupation with gullies and it was to be three years

before it was to receive its second ascent by Geoffrey Hastings.

In

1894 Haskett Smith published ‘Climbing in the British Isles: England’. This was

an A – Z of rock climbing and crammed with topographical, technical, historical

and etymological information. However this volume was of little use to anyone

seeking technical route information or descriptions. On the other hand O G

Jones book ‘Climbing in the English Lake District’ published in 1897 gave a

much fuller account of many routes which he attempted to classify according to

difficulty.

|

| Moss Ghyll |

The

Fell and Rock Climbing Club of the English Lake District was formed in 1907 and

Haskett-Smith was to become an early honorary member. Although the old guard of

the ‘Golden Age’ were beginning to fade from the foreground they were still

active. Hasket-Smith climbed his last new route in Cumberland in April 1908 at the

age of forty-nine, Haskett Gully, described in the guide as ‘very unpleasant, mossy wet and loose’,

however he continued to climb for many years after that. During its inaugural

year the F&RCC lost John Wilson Robinson who died as a result of a medical

operation and the Club formed a Memorial Committee under the chair of Haskett-Smith.

The Club through this committee organised the building of the cairn which

still stands on the Robinson’s High Level Route to Pillar and nearby a bronze

memorial tablet was set into a boulder over which Slingsby paid a final

tribute.

|

| RST Chorley 1978 |

Hasket-Smith

shared a flat with his sister near Olympia in London, they lived on independent

means but despite being a lawyer Haskett-Smith did little or no legal work.

Right up to the late 1930s he regularly joined those members of the F&RCC

who lived in or around London. In 1936 he agreed to mark the fiftieth

anniversary of his ascent of Napes Needle. He arrived in Wasdale on Good Friday

at the age of seventy-six and was met by R S T Chorley (the late Lord)

President of the F&RCC and then editor of the Alpine Journal. On the Sunday

through cold and gusty conditions and experiencing frequent snow flurries they

set off for the Needle. An audience of 300 had gathered around the Dress Circle

and Needle Gully and watched as Haskett-Smith lead by R S T Chorley up the 1886 original line of ascent and

followed by G R Speaker. Haskett-Smith

gained the summit for the last time and when someone called out ‘Tell us a

story’ he shout back ‘There is no other story. This is the top story.’ After a

short speech from Chorley and a reply from Haskett-Smith the party descended

the Needle and slowly made its way back to Wasdale where Haskett-Smith paid his

last farewell to the hills of Cumberland that he had loved so much.

|

| The forefather of British climbing, Haskett Smith |

He

died eight years later in 1946 at the grand old age of eighty-seven. He was

undoubtedly the first to realise the potential of the Lakeland fells as a

playground for the pure rock climber as well as a training ground for the

aspiring alpinist and he dedicated over fifty-seven years of his life to

developing the sport. Haskett-Smith joined the Climbers’ Club and was elected

onto the committee at the first general meeting held in London on the 28th

April 1898.

In

the June 1901 CCJ T H Sowerby takes a long look at ‘Old English Mountaineering’

and revisits some of the volumes and maps used by previous generations. It

makes fascinating reading to see just how ‘wild’ so many of the districts were

that we now regard as major tourist areas. This is illustrated with reference

to Lyson’s History 1816 in which he confirms that the ‘white-tailed eagle breeds every year in the neighbourhood of Keswick.’

Sowerby’s references go back to John Speed’s maps of 1676 and cover the main

editions that would have been of interest to the ‘tourists’ of previous

generations. Milton reports on another fatal accident to a Club member, this

time the accident happened in winter conditions on the descent from Tryfan.

Weightman, it appears, fell down, possibly the NNW Gully of the mountain.

Articles also appeared related to Savage Gully and concerning the hills of

Arran.

In

his first speech as president Haskett-Smith referred to the fact that in the

eyes of the continental mountaineering press Britain could no longer produce a `mountaineer’.

This comment, Haskett-Smith went onto explain, was proved by the fact that no

British mountaineer had been statistically recorded as summating Mont Blanc

during the previous season. The situation arose because so many members of the

Club were by then making guideless ascents and from starting points other than Chamonix. This fact was arrived at as a result of references made to the

previous President’s Book on Mont Blanc, the Journal of members’ activities and

achievements.

The

Pen-y-Gwryd was closed over Easter 1901 and also, as a result of

some very inclement weather, the Club gathered in Llanberis. The low snow line

prevented the more traditional areas around the higher summits from being

visited so some time was spent exploring Dinas Mot. On Easter Sunday an initial

exploration took place up the western gully, which from the evidence of a cairn

on the top proved it had been ascended before, however C G Brown and P A

Thomson then proceeded via a rib to climb onto the upper cliff to continue past

ledges and steep slabs to reach the summit some 200 feet above and one and a

half hours later. To round the day off the team then walked across to Lliwedd

and in full winter conditions made an ascent of Slanting Gully! [CCJ June 1901

p194]

By

then the Kyndwr Club were involved in serious cave exploration where they

carried out surveying, geological surveys, and photographic work. It was

recognised from the outset the valuable contributions that climbers made to

cave exploration and this was reinforced in an article which states, ‘here

(Mendip Hills) more than in Derbyshire, experienced rock-climbers will have the

advantage, both in getting at openings of cavities and in underground work’. [CCJ June 1901 p 198]

In

an article titled ‘British Climbing from Another Point of View’ C S Ancherson

and H V Reade both Alpine Club members discuss relevant points differentiating

rock climbing in England compared to mountaineering abroad. This article would

appear to be one of the earliest in the CCJ to address issues of a

philosophical nature. The article continues ‘Indeed

it must be borne in mind that an exaggerated estimate of the value of British

climbing in the education of the mountaineer, which is prevalent, must have been

observed by many. Everyone knows that, despite these limitations, British

climbing gives splendid sport, and that the standard of difficulty is very

high. But how far is it from reproducing the real thing?

|

| Mummeryand the Abrham Brothers on the Grepon |

|

| A new route in North Wales - climbers unknown |

The article concludes, ‘Climbing, as it is practiced in

Great Britain, forms a small sub division of rock-climbing proper, and

consequently a very small sub-section of mountaineering in the full sense of

the word. All that is commonly taught by it is the capacity to do a particular

kind of short climb, which tends to develop rock-gymnasts rather than all round

cragsmen. And, conversely, a man may be a thoroughly good all-round mountaineer

without being able to perform some of these gymnastic feats. Real

mountaineering is only to be learnt in an Alpine country, by working for

several seasons under good guides.’

[CCJ September1901 p 12]

I wonder what those esteemed authors would make of

the level of skill, or is it audacity, with which the young ‘tigers’ of today

achieve their targets and goals, not only on British rock but also in the Alps

and the Himalaya, many on their first visits to the Alps or greater ranges?

Members of the Climbers’ Club have always been on

the right side of anarchy but have not been afraid to take issue with those

authorities who take liberties, especially if it involves liberties to exercise

ones right.

The ‘Right to Roam’ issue probably had its first

airing in the September 1901 CCJ with an article entitled ‘Deer and Deer

Forests.’ The author, A L Bagley, a member of the S M C expressed his

disappointment in reading that freedom of access was granted to ‘allow the

climbing and scientific public access as far as possible.’ ‘What about

those who just want to enjoy the moors and hills?” he asks. The statement ‘as

far as possible’ referred to the damage that might have been done by the

unwary causing stags to desert the forest and move onto a neighbours land. What

Badley goes on to ask is ‘what will become of the stags on that neighbour’s

land?’ The article goes on in depth and was to be commented upon over the

following months with letters appearing in subsequent copies of the CCJ.

The Staffordshire Roaches are mentioned in the

‘Kyndwr Club Notes’ and several ’interesting scrambles’ are reported to have

been found. The Ben Nuis Chimney on Arran was climbed for the first time by

Baker, Oppenheimer and Puttrell. Under

the Editorial Notes mention was again made of the continued persistence of

those determined to construct an electric railway from Portmadoc to the foot of

Snowdon, also within the article concern is raised over the proposal to intern

the Glaslyn River in pipes to generate electricity down the Dyli Falls and that

consent had been given in the House of Commons to convert Llyn Llydaw into a

reservoir. There also appeared in the correspondence section a request for

donations to support the National Trust who wished to purchase a mile of the

western shore of Derwentwater.

|

| Charles Kingsley |

George Abraham writes about a new climb on Pillar

Rock and it is also announced that the Club will take over the publication of

'Alpina', the Swiss journal with twenty issues a year.

March 1902 saw a subtle change in the format of the

Journal there was for the first time a greater use of illustrations and

photography. There were full-page illustrations of the Great Cave Pitch in the

Gully of Craig yr Ysfa, a sketch by A E Elias and also a photograph to accompany J M A Thomson’s

account of the first ascent. Then there were the Abraham brothers’ photographs

of the cliffs of Ben Nevis from Cam Dearg, the Gap in the Tower Ridge, a

collection of four snap-shots depicting different aspects of Ben Nevis all to

illustrate an article on the history and topography of the mountain. Another

two full-page action photographs were used to good effect to accompany an

article on Wharncliffe Crags, a crag around which a variety of boulder problems

provide a ‘hard afternoon’s workout’. The purpose of the article C F

Cameron informed us was not to convey that the Don Valley was a rival to

Wasdale Head but to publicise the fact that it did provide a variety of short

climbs on hard, rough, firm-set rock, and by the experience on them the climber

would acquire a skill which would give him valuable aid in his endeavours in

the future.

The attitude of the Club towards the Deer Forest question

was raised in the Committee Notes and it was stressed that the previous article

was purely the private opinion of the writer and not that of the Club.

|

| Matterhorn, E Face |

|

| East Ridge of the Weisshorn (right) |

The Club’s fifth A G M took place at the Café

Royal, Regent St., London on the 9th May 1902, the accounts for 1901

stood at £282. 1s 6½p they were audited and passed by the meeting. Haskett-Smith

informed the Committee that Mr W Rickmer Rickmers had donated about 300 volumes

as a nucleus to form a Club library. He also referred to the gift in his

Presidential speech commenting that it was good that the Club should have its

own library as the Alpine Club had their own library. However he questioned

whether the books would be read as infrequently as those at the AC! G Winthrop

Young replied to the President’s speech referring to the fact that he was, at

that time, the youngest member of the Club. The formalities of the evening

concluded after another six speakers gave lengthy but humorous anecdotal reports

on the Club’s activities and their own adventures.

The third bound copy of the CCJ contains Volumes V

and VI of the journals and opens with a fine and extremely interesting article

by Haskett-Smith tilted ‘Wasdale Head 600 Years Ago’. It is very evident from

the article that Haskett-Smith had indeed studied Literae Humaniores! Despite routes having

been climbed on the more open buttresses as the description of

Bowfell Buttress illustrated the Club was still very much in the gully era and the

article ‘Two Gullies on Twr Du, Cader Idris’ described the first ascent on the

28th and 29th August 1902. The interesting point of this

article is in the fact that the photographs were taken by the actual climbers, J

Phillips and H L Jupp, as opposed to having been taken by a third party. After

the announcement that the Club had a nucleus of a library as donated by

Rickmers the journal of 1903 contained a catalogue reference of the volumes and

by whom they were donated. Those items donated by Rickmers were in the main of

foreign origin, where as those presented by W Maude, A V Valentine-Richards,

Godfrey W H Ellis and C W Nettleton, the Honorary Librarian, were of English

origin.

Some of our present members living in the London

region might find the article ‘A Day Down the Dene Holes’ interesting. This

described a short expedition to the ‘rural village of Bexley about 15 miles

from Charing Cross’ where there was a series of holes and underground

excavations. The team explored the labyrinth with the use of a ladder and

Alpine Lanterns and a loaded revolver just in case! No satisfactorily

explanation has ever been given for their existence, however their antiquity is

not in question as Pliny wrote about these chalk extraction in A.D. 70 and other classical writers mention them in their

works.

The Club was now entering an era of exploration of

the less frequented corners of the planet, an article on climbing in South

Africa anomalously written and submitted to the CCJ editor for fellow members to read and the library catalogue

was updated.

The sixth AGM and the W C Slingsby Years 1904 – 1907

William

Cecil Slingsby was born in 1849 into an old established and well-to-do

Yorkshire family of landowners who had reinforced the family wealth by going

into the textile industry. He grew up to love the hills and moors around his

home in the Skipton-in-Craven area and it was there that he developed his

interest for walking and a love of the outdoors. He was educated at Cheltenham

School.

In 1872 at the age of twenty-three he visited

Norway and was immediately captivated by the grandeur and splendour of the

mountains. He returned summer after summer to explore the high peaks, passes

and glaciers. Slingsby learned to speak Norwegian and to ski and in fact took

the idea of skiing to the Alps. In 1875

he made his first visit to Aak in the Romsdal Valley, he returned the following

year and went onto to make many first ascents including Kvandalstind, which he

regarded as the steepest mountain in Europe.

|

| Deep Ghyll Scafell, extreme righthand gully |

Slingsby was a member of the Provisional Committee

of the Climbers’ Club that met in February 1898 to deal with the practical

questions of detail regarding the establishment of the Club and to draft the

notice to attract new members. He then became a full committee member and was

elected to position at the first general meeting held on 28th April

1898. Not only was Slingsby known as the father of Norwegian mountaineering he

went on to become a widely acclaimed authority on Norway and in 1903 he wrote

‘Norway, the Northern Playground’.

Sadly 1928 saw the death of Cecil Slingsby, he had

continued to climb in Norway, the Alps, Scotland and the Lake District well

into the twentieth century. He moved from his Craven home to a house

overlooking Morecombe Bay and this continued to be the focal point of many

gatherings of likeminded men, including Haskett-Smith, Norman Collie, Geoffrey

Hastings, Godfrey Solly, the Hopkinsons, Pilkingtons and many others.

Slingsby’s last climb was North Climb on Pillar on his seventieth birthday in

1926. The team comprised of Raymond Bicknell who led followed by Slingsby with

Winthrop Young as last man on the rope. Winthrop Young had lost his leg whilst

serving on the Italian front; he was also Slingsby’s son-in-law having married

Eleanor Slingsby.

The First World War also sadly saw a large group of

Club members killed in action. However, the Club did survive and in fact went

from strength to strength with many fine Presidents being elected to post over

the course of time. Robert A Robinson past Committee member and ex-President of

the SMC took up the Presidency from 1907 – 1910, he was followed by Sir John

Bretland Farmer 1910 – 1912, Geoffrey Winthrop Young 1913 – 1920, A W Andrews

1920 – 1923 and George Leigh Mallory as the eighth President of the Climbers’

Club 1923 – 1924, he of course met his untimely death on Everest and has left

the Club, and the mountaineering world, pondering the everlasting question, did he die before or after

reaching the summit?

As can be seen in those early years solid pillars

for the foundations of the Club were laid down and in the main these have not

only withstood the test of time but have in fact been developed and

strengthened over the last century. 2017 will be the 120th

anniversary of the official Welsh Dinner and with that in mind I should like to

be the first to make the toast ‘And so, I give to you

‘The Climbers’ Club!’ Remember that a Club is an institution towards which

every man must contribute his share. May it flourish and prosper! CE Mathews, CC AGM 28th April 1899.

All original text has been researched in the Climbers' Club Journals, the images are based on research on the internet and were gathered from the following sites:-

The Yorkshire Ramblers

The Scottish Mountaineering Club

The Fell & Rock Climbing Club

FootlessCrow.blogspot.com

History of British Climbing

The British Mountaineering Council

The Armitt Museum

SummitPost.org

Abraham Brothers Photographic Collection

UK Climbing.com

The Yorkshire Ramblers

The Scottish Mountaineering Club

The Fell & Rock Climbing Club

FootlessCrow.blogspot.com

History of British Climbing

The British Mountaineering Council

The Armitt Museum

SummitPost.org

Abraham Brothers Photographic Collection

UK Climbing.com

There are a couple of typos in the paragraph about Arthur Bagley's "Deer and Deer Forests" article: in one instance you call him "Badley"; and he was a member of the CC not the SMC.

ReplyDelete